Brian E. Frydenborg is an American freelance writer and consultant from the New York City area who holds an MS in Peace Operations and specializes in international and US policy, security, conflict, terrorism and counterterrorism, humanitarianism, development, social justice, and history. He just returned to the United States after over five years in the Middle East. You can follow and contact him on Twitter: @bfry1981 and at his news site: Real Context News.

Topics

The Great AI Disruption in the Workplace: What to Expect and How to Prepare for It

Studies, including our own, reveal that as companies prepare for future needs and trends, they plan to focus on digital upskilling to help enable employees through technology. 52 percent of L&D leaders ranked “Digital Upskilling” as their highest priority for 2019. So, as we look ahead at 2020, we invited Brian E. Frydenborg, a consultant on international and U.S. policy and politics and development, to get his take on what AI will mean in the workplace, how to best prepare employees and review where the responsibilities lie.

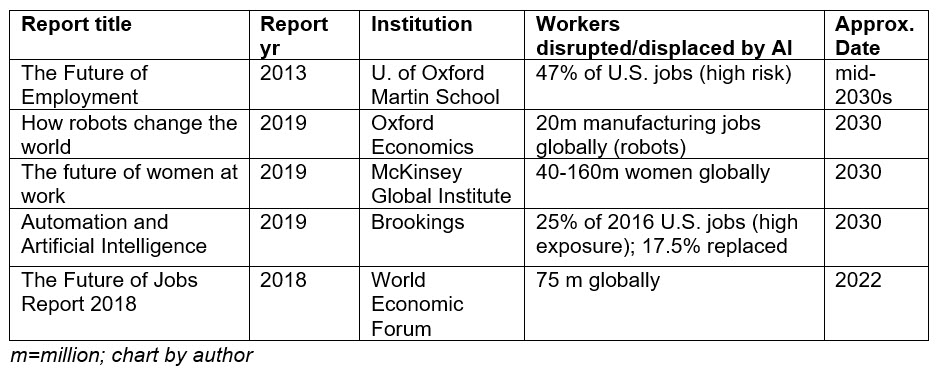

A recent Forbes article summarized a number of current studies about the coming impact of artificial intelligence (AI) on various segments of the global workforce.

While there will be massive benefits to come from AI, via new jobs as discussed in the Forbes piece, unless concerted efforts are planned and executed, many of the people will be hit as if by a freight train, stranded by AI with little to no viable professional path forward.

The below chart summarizes some of the most alarming possibilities and includes an additional Brookings study:

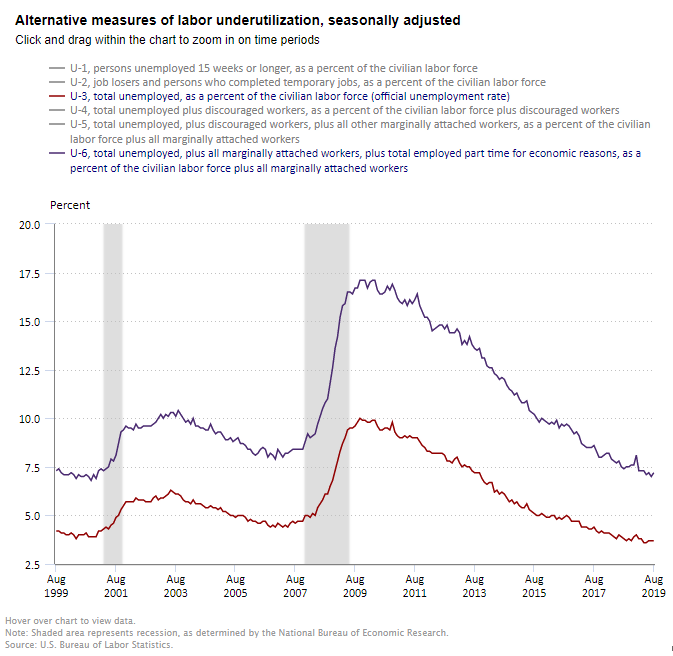

Of course, we are already seeing signs of this, as is evident from several telling statistics’ evolutions.

A tale of labor statistics

In 1999, the labor force participation rate (the portion of working-age adults working or looking for work, with some exclusions) was 67%; at the start of the Great Recession, that had already fallen to 66%, and now it is 63%.

The story behind this statistic? Often, people who have been unable to find work after a long period of time give up looking for work, meaning they are taken out of the pool of people categorized as either “employed” or “unemployed.” There are other factors, too, such as health and disability, and portions of this group remain something of an enigma. While there are positives about the economy under the current administration, this statistic deflates the unemployment rate and masks the fact that millions of Americans are unable to find suitable work.

The other key statistic? Underemployment, when workers are working below their skill level or are only working part-time but would rather (or need!) to work full-time (as a freelance writer and consultant, I can personally attest to this being a thing). This one is a bit tricky, since there is no agreed-upon official number as there is with unemployment. While unemployment sits at 3.7% for this summer, one of several alternative Department of Labor measurements factoring in some of the underemployed nearly doubles this statistic to 7.2%. There are other measurements that put have put that rate far higher in recent years, even well over 12%, and it is a particular problem for minorities and young adults, even college graduates. The ratio of underemployed to unemployed workers has also increased significantly since the Great Recession.

The emergence of the gig economy is very telling, too. According to Gallup, over one-third of the U.S. workforce (36%) are in the gig economy and 29% have a gig job as their primary employment. This portion has grown rapidly and is expected to continue climbing, but many gig workers are finding old employment classifications, regulations and tax arrangements to be inadequate, with benefits remaining elusive.

The authors of the Oxford University study cited in the first chart corrected some of their earlier thoughts about the gig economy from the Great Recession, realizing that much of the growth of the gig economy (which may now be contracting) was underemployment personified: stop-gap efforts of people unable to find rewarding full-time careers, a revelation highlighted by Gartner in a post to start 2019.

No wonder some seven million open jobs are left unfilled and have been so for some time in America.

Why does the U.S. have such a troubling skills gap?

Identifying a massive problem does not solve it, that requires understanding why there is such a skills gap in the first place. Let’s take a quick look at the issue, by the numbers:

- About 108 million American workers (82% of the total workforce) hold jobs that require moderate or high digital knowledge, according to a 2018 Brookings Institution report and jobs are increasingly likely to require higher levels of technical knowledge.

- An example of this issue comes from the Manufacturing Institute at the National Association of Manufacturers- retirements and new growth will require 3.5 million new manufacturing jobs to be filled by 2025, but if present trends hold, as many as 2 million of those jobs are expected to go unfilled.

- Policymakers are increasingly worried that automation will strike across industry lines, far beyond manufacturing. Autonomous vehicles are the most visible example of a clear threat to existing industries: A 2018 McKinsey & Co. forecast estimates that as many as 800 million people worldwide could lose their jobs to automation in the next dozen years.

Two answers are education and inequality.

Education matters for job prospects, performance, and career development. When students perform better, they are often able to obtain scholarships or admissions to schools that top employers find more attractive. For some who cannot afford college or are wary of taking on burdensome student loans, scholarships or grants dependent on their performance may be their only option to attend college, and outcomes for people who only have a high-school education or less are drastically worse.

Thus, the skills gap can in large part be explained by the socio-economic health of our nation: struggling schools, struggling communities, and vastly unequal divides are going to leave massive gaps in America, not least of all a skills gap.

But there are more complex answers that may be just as valid.

The same post cited above from Gartner pointed to new research suggesting that employers had brought on much of the growth of the skills gap through their own hiring practices. Since during the Great Recession there was a massive increase in people out of work and desperate for jobs, employers felt they could dramatically raise the bar of what they were looking for even while not offering more, or even offering less, for such positions. I recall a discussion with several Edelman executives back in 2013 in which they told me they could take on master’s degree-holders as paid interns simply because the job market was favorable to employers. In other words, there was no sudden need for far more skilled workers, that is just what companies have felt the climate permitted. In the United States, hiring workers used to be about starting relationships focused on growth on both ends, helping workers grow into roles.

No shortage of proposals but little action

Given what has been discussed here, it is clear legislation can make an enormous difference.

There are no shortages of bills, even bipartisan ones: all have the goal of building skills for the future, improving on-the-job training, creating pathways for lifelong learning and making college more affordable. While gridlock still reigns supreme, Andrew Yang, a 2020 presidential candidate who is far more skeptical of job retraining programs has a unique proposal for a universal basic income, which one advocate calls “a Social Security for the 21st century.” He has framed this as his primary defense against the future ravages of AI.

And some candidates dismiss concerns about robots and automation altogether: “Germany has nearly five times as many robots per worker as we do and has not lost jobs overall as a result,” writes Elizabeth Warren. Similar to Biden and echoing some of his emphases, she frequently mentions “training” or a derivative, calling for a “tenfold” increase in funding for apprenticeships and the creation of a federal Department of Economic Development to help coordinate training and other domestic economic initiatives.

Legislation and the Private Sector can lead the way (but it’s complicated)

One MIT Sloan article noted that companies can view the AI shift as a way to redefine their ethical relationships with their employees. This is, of course, a wonderful proposal, but the government passing stricter regulations about how workers can be treated and offering incentives like tax breaks are also going to be a necessary part of any hope of major reform within the private sector.

Not all government solutions need to come from the federal government. As the coming AI revolution will have vastly different effects depending on the locale, and since America has an extremely diverse array of sub-economies, certain cities, towns, and regions will face more potentially negative impacts from AI than others, and can and should plan accordingly. In the words of another MIT Sloan--published piece, four pillars are needed: “a vision for responding to technological change; a city administration able to activate new plans; a strong foundation of top talent, top employers, and top educational institutions; and the momentum to seize new opportunities.”

At all levels, adjustments to be triggered by the Great AI Disruption will touch millions of workers worldwide. It remains to be seen if any of the proposals will be enacted, and while there is plenty of agreement on the need for drastic action, consensus on what action to take remains as elusive as the filling of the roughly seven million open job postings representing America’s skills gap.

Additional Resources:

Brian E. Frydenborg is an American freelance writer and consultant from the New York City area who holds an MS in Peace Operations and specializes in international and US policy, security, conflict, terrorism and counterterrorism, humanitarianism, development, social justice, and history. He just returned to the United States after over five years in the Middle East. You can follow and contact him on Twitter: @bfry1981 and at his news site: Real Context News.